Force Equation: 7 Powerful Insights You Must Know

Ever wondered what makes things move or stop? The answer lies in the force equation — a simple yet revolutionary concept that shapes our understanding of motion, energy, and the universe itself.

Understanding the Force Equation: The Foundation of Motion

The force equation, commonly expressed as F = ma, is one of the most fundamental principles in physics. It was first formalized by Sir Isaac Newton in his Second Law of Motion and remains a cornerstone in classical mechanics. This equation states that the force acting on an object is equal to the mass of the object multiplied by its acceleration.

Breaking Down F = ma

Each component of the force equation plays a crucial role in determining how objects behave under applied forces. Let’s dissect each variable:

- F (Force): Measured in newtons (N), this represents the push or pull acting on an object.

- m (Mass): Measured in kilograms (kg), mass is the amount of matter in an object and determines its resistance to acceleration.

- a (Acceleration): Measured in meters per second squared (m/s²), this is the rate at which an object’s velocity changes over time.

When you apply a force to an object, its acceleration depends directly on the object’s mass. A heavier object requires more force to achieve the same acceleration as a lighter one. This intuitive relationship is precisely what the force equation quantifies.

“The great book of nature is written in the language of mathematics.” — Galileo Galilei

Historical Development of the Force Equation

While Newton is credited with formalizing the force equation, the concept of force and motion evolved over centuries. Ancient Greek philosophers like Aristotle believed that a continuous force was necessary to maintain motion — a view later disproven by Galileo and refined by Newton.

Galileo’s experiments with inclined planes laid the groundwork for understanding inertia and acceleration. His observations showed that objects accelerate uniformly under gravity, independent of their mass — a key insight that Newton later expanded upon. By combining Galileo’s kinematic findings with Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, Newton developed a unified theory of motion and gravitation.

His 1687 publication, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), introduced the three laws of motion, with the second law providing the mathematical foundation for the force equation. You can explore the original text via this digital archive.

Applications of the Force Equation in Real Life

The force equation isn’t just a theoretical construct — it’s applied daily in engineering, transportation, sports, and even medicine. From designing safer cars to optimizing athletic performance, F = ma helps us predict and control motion.

Automotive Safety and Crash Testing

In car design, engineers use the force equation to calculate the impact forces during collisions. By knowing the mass of a vehicle and its rate of deceleration upon impact, they can estimate the force exerted on passengers.

This information guides the development of crumple zones, airbags, and seatbelts — all designed to reduce the force experienced by occupants. For example, extending the time over which deceleration occurs (via crumple zones) reduces peak force, minimizing injury risk. The relationship is derived from the impulse-momentum theorem, which is directly linked to the force equation.

Organizations like the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) use these principles in crash test simulations to improve vehicle safety standards.

Sports Science and Athletic Training

Athletes and coaches apply the force equation to enhance performance. In sprinting, for instance, maximizing acceleration requires applying large forces against the ground. Since mass is relatively constant, increasing force output leads to greater acceleration.

Strength training programs are designed to increase muscular force production, thereby improving explosive movements in sports like football, basketball, and track. Biomechanists use motion-capture technology and force plates to measure ground reaction forces and calculate acceleration, providing data-driven feedback to athletes.

For example, a study published by the Journal of Applied Biomechanics demonstrated how sprinters who generated higher horizontal forces achieved faster start times — a direct application of F = ma.

Types of Forces and Their Equations

While F = ma describes the net force acting on an object, there are many specific types of forces that contribute to this net value. Each has its own equation and physical origin, but all must conform to the overarching force equation when analyzing motion.

Gravitational Force

One of the most familiar forces is gravity. The gravitational force between two masses is given by Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation:

F = G × (m₁m₂)/r²

Where G is the gravitational constant (6.674 × 10⁻¹¹ N·m²/kg²), m₁ and m₂ are the masses, and r is the distance between their centers. On Earth’s surface, this simplifies to F = mg, where g ≈ 9.8 m/s² is the acceleration due to gravity.

This version of the force equation explains why all objects fall at the same rate in a vacuum — because while heavier objects experience greater gravitational force, their greater mass exactly offsets this in F = ma, resulting in the same acceleration.

Frictional Force

Friction opposes motion and is critical in everyday activities like walking or driving. The force of kinetic friction is calculated as:

F_friction = μ_k × N

Where μ_k is the coefficient of kinetic friction and N is the normal force (the force pressing the surfaces together). Static friction, which prevents motion from starting, can vary up to a maximum of μ_s × N.

When analyzing motion on a surface, the net force in the horizontal direction becomes F_applied – F_friction, which then determines acceleration via F_net = ma. This is essential in designing brakes, tires, and even shoe soles.

For more on friction coefficients, refer to engineering databases like Engineering Toolbox.

Normal and Tension Forces

The normal force is the support force exerted by a surface perpendicular to an object. On a flat surface, it equals the object’s weight (mg), but on an incline, it becomes mg·cos(θ), where θ is the angle of the slope.

Tension force occurs in ropes, cables, or strings when they are pulled tight. In systems like pulleys or elevators, tension must be calculated to ensure structural integrity. For example, in an elevator accelerating upward, the tension in the cable is T = m(g + a), derived directly from applying the force equation to the system.

These forces are vital in construction, robotics, and mechanical engineering, where load distribution and stress analysis rely on accurate force calculations.

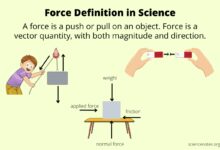

Vector Nature of Force and Directional Analysis

Force is not just a number — it’s a vector quantity, meaning it has both magnitude and direction. This is critical when applying the force equation in real-world scenarios where multiple forces act simultaneously.

Resolving Forces into Components

When forces act at angles, they must be broken down into horizontal (x) and vertical (y) components using trigonometry. For a force F at angle θ:

- F_x = F·cos(θ)

- F_y = F·sin(θ)

These components are then used in separate force equations for each direction: ΣF_x = ma_x and ΣF_y = ma_y. This allows physicists and engineers to analyze complex motions, such as projectile trajectories or vehicles navigating curves.

For example, when a sled is pulled at an angle across snow, only the horizontal component contributes to forward acceleration, while the vertical component affects the normal force and thus friction.

Net Force and Equilibrium

The force equation applies to the net force — the vector sum of all forces acting on an object. If ΣF = 0, then acceleration is zero, meaning the object is either at rest or moving at constant velocity (Newton’s First Law).

This state is called equilibrium. In static equilibrium (no motion), forces balance in all directions. In dynamic equilibrium (constant velocity), forces still balance, but the object is moving.

Understanding net force is essential in structural engineering. For instance, bridges must be designed so that all forces — tension, compression, gravity, wind — sum to zero under normal conditions to prevent collapse.

“For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.” — Newton’s Third Law

Advanced Applications: Beyond Classical Mechanics

While the classical force equation F = ma is incredibly powerful, modern physics extends its application into relativistic and quantum domains, where modifications are necessary.

Relativistic Force Equation

In Einstein’s theory of special relativity, mass increases with velocity as an object approaches the speed of light. Therefore, the simple F = ma no longer holds. Instead, force is defined as the rate of change of relativistic momentum:

F = dp/dt, where p = γmv and γ = 1/√(1 – v²/c²)

As velocity increases, γ grows, requiring ever more force to produce further acceleration. This explains why no object with mass can reach the speed of light — it would require infinite force.

This relativistic correction is crucial in particle accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider, where protons travel at 99.999999% of light speed. You can learn more about relativistic mechanics from HyperPhysics.

Quantum and Field Theories

In quantum mechanics, the concept of force is less direct. Instead of forces, interactions are described by the exchange of virtual particles — photons for electromagnetic force, gluons for strong force, etc.

The classical force equation doesn’t apply at subatomic scales, where uncertainty and wave-particle duality dominate. However, the expectation values of forces can still be calculated using quantum field theory, which unifies quantum mechanics and special relativity.

For example, the Coulomb force between two electrons can be derived from quantum electrodynamics (QED), providing more accurate predictions than classical physics in high-energy scenarios.

Common Misconceptions About the Force Equation

Despite its simplicity, the force equation is often misunderstood. Clarifying these misconceptions is essential for proper application in science and engineering.

Force Causes Velocity (Myth)

Many people believe that force produces velocity, but this is incorrect. Force produces acceleration — a change in velocity. An object can move at constant velocity with zero net force (e.g., a spacecraft coasting in space).

This misconception stems from everyday experiences where friction is always present. On Earth, you need to keep pushing a shopping cart to keep it moving, not because motion requires force, but because friction opposes it. In space, no continuous force is needed to maintain motion.

Mass vs. Weight Confusion

Mass and weight are often used interchangeably, but they are different. Mass is an intrinsic property measured in kilograms, while weight is the gravitational force on that mass, measured in newtons.

Weight is calculated using the force equation: W = mg. On the Moon, your mass is the same, but your weight is less because g is smaller. This distinction is crucial in physics and engineering calculations.

Force Equation Only Applies to Linear Motion

Some assume F = ma only works for straight-line motion, but it applies to any direction of acceleration. In circular motion, for example, centripetal force is given by F = mv²/r, which is still a form of F = ma, where a = v²/r is the centripetal acceleration.

This principle governs everything from planetary orbits to roller coaster loops. Engineers use it to design safe curves on roads and racetracks.

Teaching the Force Equation: Strategies and Tools

Effectively teaching the force equation requires hands-on experiments, visual aids, and real-world examples to help students grasp abstract concepts.

Classroom Demonstrations

Simple experiments like using spring scales to pull carts of different masses across a table can illustrate how force and mass affect acceleration. Motion sensors and data loggers allow students to collect real-time data and verify F = ma experimentally.

Another popular demo involves dropping objects of different masses in a vacuum chamber to show that they fall at the same rate — reinforcing the relationship between gravitational force and inertia.

Digital Simulations and Interactive Tools

Online platforms like PhET Interactive Simulations offer free, research-based tools that let students manipulate variables in the force equation and observe outcomes in real time.

For example, the “Forces and Motion: Basics” simulation allows users to push objects, add friction, and see force diagrams update dynamically. These tools enhance conceptual understanding and engagement, especially for visual learners.

Problem-Solving Frameworks

Teaching students a structured approach to solving force problems improves accuracy and confidence. A common method includes:

- Draw a free-body diagram showing all forces.

- Choose coordinate axes and resolve forces into components.

- Apply ΣF_x = ma_x and ΣF_y = ma_y.

- Solve the equations algebraically.

- Check units and reasonableness of the answer.

This systematic process is used in AP Physics, engineering courses, and competitive exams worldwide.

Force Equation in Engineering and Technology

From skyscrapers to smartphones, the force equation underpins modern technology. Engineers use it to ensure structures can withstand loads, machines operate efficiently, and devices respond accurately to user input.

Structural and Civil Engineering

In building design, engineers calculate the forces acting on beams, columns, and foundations. Wind loads, seismic forces, and the weight of materials all contribute to the net force that a structure must resist.

Using F = ma in dynamic analysis, they simulate how buildings respond to earthquakes. By modeling acceleration patterns, they can design damping systems that reduce destructive forces.

Organizations like the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) publish standards based on force calculations to ensure public safety.

Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering

Rocket scientists rely heavily on the force equation to calculate thrust. The thrust force must exceed the rocket’s weight (mg) to achieve liftoff. Once airborne, F = ma determines how quickly the rocket accelerates into orbit.

Jet engines, car engines, and even drones use similar principles. The net force generated by propulsion systems dictates acceleration, climb rate, and maneuverability.

For instance, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket produces over 7.6 million newtons of thrust at liftoff, enabling it to accelerate a 500,000 kg vehicle against Earth’s gravity.

Robotics and Automation

In robotics, actuators must generate precise forces to move limbs or manipulate objects. The force equation helps determine motor torque, gear ratios, and power requirements.

For example, a robotic arm lifting a 10 kg object vertically must exert a force greater than 98 N (F = mg) to accelerate it upward. Sensors measure actual force and acceleration, allowing feedback control systems to adjust in real time.

This precision is vital in applications like surgical robots, where even small force errors can have serious consequences.

What is the force equation?

The force equation is F = ma, which states that the net force acting on an object equals its mass multiplied by its acceleration. It is Newton’s Second Law of Motion and is fundamental in physics and engineering.

How is the force equation used in everyday life?

The force equation is used in car safety design, sports performance analysis, elevator mechanics, and even in walking or jumping. It helps engineers and scientists predict how objects will move when forces are applied.

Does the force equation work in space?

Yes, the force equation works in space. In fact, it’s essential for calculating spacecraft trajectories, orbital maneuvers, and re-entry dynamics. The absence of air resistance makes F = ma even more directly applicable.

Can the force equation be used for rotating objects?

For rotational motion, a similar equation exists: τ = Iα (torque = moment of inertia × angular acceleration). While different in form, it’s the rotational analog of F = ma and follows the same conceptual framework.

Is force a scalar or vector quantity?

Force is a vector quantity — it has both magnitude and direction. This is why vector addition is required when calculating net force in multi-force systems.

Understanding the force equation is not just about memorizing F = ma. It’s about grasping how the universe responds to pushes and pulls, from the smallest particles to the largest galaxies. Whether you’re a student, engineer, or curious mind, mastering this equation opens the door to deeper insights into motion, energy, and the laws that govern our reality.

Further Reading: