Force Formula: 7 Powerful Insights You Must Know

Ever wondered why things move, stop, or accelerate? It all comes down to one fundamental concept: the force formula. In this deep dive, we’ll unpack everything you need to know about force, its formula, real-world applications, and why it’s a cornerstone of physics.

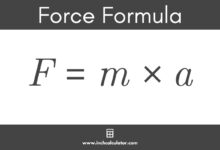

Understanding the Force Formula: The Basics

The force formula is one of the most essential equations in physics, serving as the backbone for understanding motion and interaction between objects. At its core, the force formula is expressed as F = ma, where F stands for force, m for mass, and a for acceleration. This equation, derived from Newton’s Second Law of Motion, reveals how force influences the movement of objects in our universe.

What Is Force?

Force is any interaction that, when unopposed, changes the motion of an object. It can cause an object with mass to accelerate, decelerate, or change direction. Forces are vector quantities, meaning they have both magnitude and direction. This dual nature is crucial when calculating net forces in multi-directional systems.

- Force is measured in newtons (N), named after Sir Isaac Newton.

- One newton equals the force required to accelerate a 1-kilogram mass by 1 m/s².

- Forces can be contact-based (like friction) or non-contact (like gravity).

“Force is not just a push or pull; it’s the language through which objects communicate motion.” – Physics Educator

Breaking Down F = ma

The formula F = ma is deceptively simple but profoundly powerful. It tells us that the force applied to an object is directly proportional to both its mass and its acceleration. If you double the mass while keeping acceleration constant, the force doubles. Similarly, doubling acceleration with the same mass also doubles the force.

- Mass (m) is the amount of matter in an object, measured in kilograms (kg).

- Acceleration (a) is the rate of change of velocity, measured in meters per second squared (m/s²).

- Force (F) is the result, measured in newtons (N).

For example, if a 10 kg object accelerates at 3 m/s², the force applied is 30 N. This straightforward calculation underpins everything from car safety design to rocket science.

Newton’s Laws and the Force Formula

The force formula doesn’t exist in isolation—it’s deeply rooted in Newton’s three laws of motion. These laws form the foundation of classical mechanics and explain how forces govern motion in everyday life and beyond.

Newton’s First Law: Inertia

Also known as the law of inertia, this principle states that an object at rest stays at rest, and an object in motion stays in motion unless acted upon by an external force. This law introduces the concept of net force and explains why forces are necessary to change motion.

- Inertia is the resistance of any physical object to change in its velocity.

- This law explains why seatbelts are crucial—they counteract inertia during sudden stops.

- Spacecraft in orbit continue moving because there’s minimal friction in space.

While this law doesn’t directly involve the force formula, it sets the stage for understanding when and why forces are needed.

Newton’s Second Law: The Core of the Force Formula

This is where F = ma shines. Newton’s Second Law states that the acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the net force acting on it and inversely proportional to its mass. This law quantifies motion and allows precise predictions in engineering and physics.

- The direction of acceleration is the same as the direction of the net force.

- If multiple forces act on an object, the net force is the vector sum of all forces.

- This law is used in designing everything from elevators to roller coasters.

For instance, when engineers design a car, they use the force formula to calculate how much force the engine must generate to achieve desired acceleration, factoring in the vehicle’s mass and resistance forces like air drag.

Newton’s Third Law: Action and Reaction

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. This law explains interactions between two objects. When Object A exerts a force on Object B, Object B simultaneously exerts an equal and opposite force on Object A.

- This law is why rockets can propel themselves in space—expelling gas backward creates forward thrust.

- Walking is possible because your foot pushes the ground backward, and the ground pushes you forward.

- It emphasizes that forces always occur in pairs.

While not directly part of the force formula, this law ensures that forces are never isolated, which is critical when analyzing systems with multiple interacting bodies.

Types of Forces and Their Formulas

The force formula F = ma applies universally, but different types of forces have their own specific equations and characteristics. Understanding these variations is key to solving real-world physics problems.

Gravitational Force

Gravity is the force that attracts two masses toward each other. On Earth, it gives weight to objects and keeps planets in orbit. The gravitational force between two objects is given by Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation:

F = G × (m₁m₂)/r²

- G is the gravitational constant (6.674 × 10⁻¹¹ N·m²/kg²).

- m₁ and m₂ are the masses of the two objects.

- r is the distance between their centers.

On Earth’s surface, this simplifies to F = mg, where g is the acceleration due to gravity (approximately 9.8 m/s²). This is a direct application of the force formula, where weight is the force of gravity acting on mass.

Learn more about gravitational force at Encyclopedia Britannica.

Frictional Force

Friction opposes motion between surfaces in contact. It’s essential for walking, driving, and stopping vehicles. The force of friction is calculated as:

F_friction = μ × F_normal

- μ (mu) is the coefficient of friction, depending on the materials in contact.

- F_normal is the normal force, usually equal to the object’s weight on a flat surface.

Static friction prevents motion from starting, while kinetic friction acts when an object is already moving. Both are crucial in safety engineering and material science.

For example, car tires are designed with high μ values to maximize grip, especially in wet conditions. This directly ties into the force formula when calculating stopping distances and braking forces.

Normal Force and Tension

The normal force is the support force exerted by a surface on an object in contact with it. It’s perpendicular (normal) to the surface. For an object resting on a flat surface, the normal force equals the object’s weight (mg).

- On an inclined plane, the normal force is less than the weight and depends on the angle of incline.

- Tension is the force transmitted through a string, rope, or cable when it’s pulled tight.

- Tension is uniform in massless, inextensible ropes in ideal physics problems.

These forces are often components in free-body diagrams, which are essential tools for applying the force formula in complex systems.

Applications of the Force Formula in Real Life

The force formula isn’t just a classroom concept—it’s used daily in engineering, sports, transportation, and technology. Understanding how F = ma applies in real-world scenarios makes physics tangible and relevant.

Automotive Engineering and Safety

Car manufacturers rely heavily on the force formula to design safer, more efficient vehicles. Crash tests, acceleration performance, and braking systems all depend on precise force calculations.

- During a collision, the force experienced by passengers depends on the deceleration and the time over which it occurs—this is why airbags increase safety by extending the time of impact.

- Engineers calculate the force needed for a car to accelerate from 0 to 60 mph in a certain time, using F = ma and adjusting for engine power and friction.

- Anti-lock braking systems (ABS) optimize frictional force to prevent skidding.

For more on automotive physics, visit HowStuffWorks.

Space Exploration and Rocket Science

Rockets are perhaps the most dramatic application of the force formula. To escape Earth’s gravity, a rocket must generate enough thrust (force) to accelerate its massive structure upward.

- Thrust is produced by expelling exhaust gases at high speed, following Newton’s Third Law.

- The force formula helps calculate the acceleration of a rocket as it burns fuel and loses mass.

- Engineers use F = ma to determine fuel requirements and trajectory adjustments.

NASA and private space companies like SpaceX use these principles to launch satellites, send probes to Mars, and plan crewed missions.

Sports and Human Performance

Even athletes use the force formula, often intuitively. Whether it’s a sprinter exploding off the blocks or a basketball player jumping for a dunk, force, mass, and acceleration are at play.

- Coaches analyze an athlete’s force production to improve performance and reduce injury risk.

- Weightlifters generate massive forces to accelerate barbells upward, with F = ma determining the required effort.

- Biomechanists study ground reaction forces to optimize running techniques.

For example, a 70 kg sprinter accelerating at 4 m/s² generates 280 N of force with each stride—this insight helps design better training programs.

Common Misconceptions About the Force Formula

Despite its simplicity, the force formula is often misunderstood. Clarifying these misconceptions is crucial for accurate application in both academic and real-world contexts.

Force Equals Motion (Myth)

Many people believe that force causes motion, but this is incomplete. Force causes acceleration, not motion itself. An object can move at constant velocity with zero net force (thanks to inertia).

- A car moving at 60 mph on a highway has balanced forces (engine force vs. air resistance), so net force is zero.

- Force is only needed to change speed or direction, not to maintain motion.

- This misconception stems from everyday experiences where friction always acts, requiring constant force to keep moving.

Understanding this distinction is vital for correctly applying the force formula in physics problems.

Mass vs. Weight Confusion

People often use mass and weight interchangeably, but they are different. Mass is a scalar (amount of matter), while weight is a force (mass × gravity).

- An astronaut has the same mass on Earth and the Moon but weighs less on the Moon due to lower gravity.

- The force formula uses mass, not weight—confusing the two leads to calculation errors.

- Weight is measured in newtons; mass in kilograms.

When using F = ma, always ensure mass is in kg, not in pounds or other weight units.

Ignoring Vector Nature of Force

Force is a vector, so direction matters. A common mistake is treating forces as scalars and adding them algebraically without considering direction.

- In a tug-of-war, if both teams pull with 500 N in opposite directions, the net force is zero.

- On an inclined plane, forces must be resolved into components using trigonometry.

- Free-body diagrams are essential tools to visualize vector forces before applying the force formula.

Ignoring vectors leads to incorrect net force calculations and flawed predictions of motion.

Advanced Concepts: Beyond F = ma

While F = ma is foundational, advanced physics extends the force formula into more complex domains, including relativity, quantum mechanics, and fluid dynamics.

Relativistic Force

In Einstein’s theory of relativity, as objects approach the speed of light, their mass increases, and Newton’s laws no longer apply directly. The relativistic force formula becomes more complex:

F = dp/dt, where p is relativistic momentum (p = γmv, and γ is the Lorentz factor).

- At high speeds, acceleration decreases even with constant force due to increasing mass.

- This effect is negligible at everyday speeds but critical in particle accelerators.

- The Large Hadron Collider uses these principles to accelerate protons to 99.99% the speed of light.

For more on relativity, see Space.com.

Force in Fluid Dynamics

In fluids, forces arise from pressure, viscosity, and flow. The Navier-Stokes equations describe fluid motion and include force terms for pressure gradients and viscous stresses.

- Lift force on an airplane wing is calculated using Bernoulli’s principle and Newton’s laws.

- Drag force opposes motion through fluids and depends on velocity, shape, and fluid density.

- Engineers use computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to simulate these forces in aircraft and car design.

These applications show how the force formula evolves in specialized fields.

Quantum Forces and Fundamental Interactions

At the subatomic level, forces are mediated by particles. The four fundamental forces—gravitational, electromagnetic, strong nuclear, and weak nuclear—govern all interactions.

- The electromagnetic force, for example, is carried by photons and explains chemical bonding.

- While F = ma doesn’t directly apply to quantum particles, the concept of force remains central.

- Physicists use field theories like quantum electrodynamics (QED) to describe these interactions.

These advanced theories build upon the classical force formula, extending its reach to the smallest scales.

How to Solve Force Formula Problems Step by Step

Mastering the force formula requires a systematic approach. Whether you’re a student or a professional, following a clear problem-solving strategy ensures accuracy and deep understanding.

Step 1: Identify the System and Forces

Begin by defining the object or system you’re analyzing. Then, list all forces acting on it—gravity, normal force, friction, tension, applied force, etc.

- Draw a free-body diagram to visualize forces as arrows.

- Label each force clearly and indicate its direction.

- Ignore forces acting on other objects unless they’re connected.

This step prevents missing key forces that affect the net force.

Step 2: Apply Newton’s Second Law

Write the equation ΣF = ma for each direction (x, y, z). Break forces into components if necessary using trigonometry.

- If forces are balanced (ΣF = 0), acceleration is zero (constant velocity or at rest).

- If unbalanced, solve for acceleration using a = ΣF/m.

- Use consistent units: kg, m/s², N.

This is the core application of the force formula.

Step 3: Solve and Interpret Results

Perform the calculations and check if the answer makes sense. Does the direction of acceleration match the net force? Is the magnitude realistic?

- Double-check unit conversions and vector signs.

- Consider real-world constraints (e.g., maximum friction).

- Practice with varied problems to build intuition.

Resources like Khan Academy offer excellent practice problems.

What is the force formula?

The force formula is F = ma, where F is force in newtons (N), m is mass in kilograms (kg), and a is acceleration in meters per second squared (m/s²). It is derived from Newton’s Second Law of Motion and describes how force affects the motion of an object.

How do you calculate force in newtons?

To calculate force in newtons, multiply the mass of an object (in kg) by its acceleration (in m/s²). For example, a 5 kg object accelerating at 2 m/s² experiences a force of 10 N (F = 5 × 2 = 10).

Is weight the same as force?

Weight is a type of force—the force of gravity acting on a mass. Weight is calculated as W = mg, where g is the acceleration due to gravity (9.8 m/s² on Earth). So, while all weights are forces, not all forces are weights.

Can the force formula be used in space?

Yes, the force formula F = ma applies everywhere, including space. Astronauts and spacecraft experience forces even in microgravity. For example, a rocket in space uses thrust (force) to accelerate, following F = ma regardless of the absence of air or gravity.

What are the limitations of F = ma?

F = ma is accurate for macroscopic objects at speeds much slower than light. It doesn’t apply in relativistic conditions (near light speed) or quantum scales. Additionally, it assumes constant mass, which isn’t true for systems like rockets that lose mass as fuel burns.

Understanding the force formula is essential for mastering physics and engineering. From everyday motion to space exploration, F = ma provides a powerful tool for analyzing and predicting how objects move. By exploring its foundations, applications, and advanced extensions, we gain a deeper appreciation for the invisible forces shaping our world. Whether you’re solving homework problems or designing the next Mars rover, the force formula remains a cornerstone of scientific thought.

Further Reading: