Force of Gravity Equation: 7 Shocking Truths Revealed

Ever wondered why things fall down and not up? The answer lies in one of the most fundamental concepts in physics—the force of gravity equation. It’s not just about apples falling from trees; it shapes galaxies, governs planetary motion, and keeps us grounded—literally.

Understanding the Force of Gravity Equation: A Foundational Overview

The force of gravity equation is one of the cornerstones of classical physics, first formally described by Sir Isaac Newton in the late 17th century. At its core, this equation explains how two masses attract each other across space. While it may sound simple, its implications are vast and deeply embedded in our understanding of the universe.

What Is the Force of Gravity Equation?

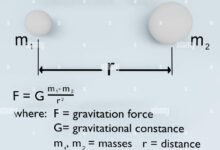

The standard form of the force of gravity equation is expressed as:

F = G frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}

Where:

- F is the gravitational force between two objects,

- G is the gravitational constant (6.67430 × 10⁻¹¹ N·m²/kg²),

- m₁ and m₂ are the masses of the two objects,

- r is the distance between the centers of the two masses.

This inverse-square law means that the force weakens rapidly as distance increases. For example, doubling the distance reduces the gravitational force to a quarter of its original strength.

Historical Development of the Equation

While gravity has always existed, the mathematical formulation began with Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687). Before Newton, Galileo had observed that all objects fall at the same rate regardless of mass, but it was Newton who unified celestial and terrestrial mechanics.

He proposed that the same force causing an apple to fall also keeps the Moon in orbit around Earth. This revolutionary idea bridged the gap between Earth-bound physics and cosmic phenomena. You can read more about Newton’s original work through the Wikisource archive of Principia.

Why the Force of Gravity Equation Matters Today

Even in the age of Einstein’s general relativity, Newton’s force of gravity equation remains incredibly useful. Engineers use it to calculate satellite trajectories, physicists apply it in astrophysical models, and educators rely on it to teach fundamental mechanics.

It’s accurate enough for most real-world applications—like launching rockets or predicting tides—unless dealing with extreme conditions such as black holes or near-light speeds, where Einstein’s theory takes over.

Breaking Down the Components of the Force of Gravity Equation

To truly grasp the power and precision of the force of gravity equation, we must dissect each variable and understand its role in shaping gravitational interactions.

The Gravitational Constant (G)

Often called “Big G,” the gravitational constant is a proportionality factor that determines the strength of gravity in the universe. Unlike “little g” (9.8 m/s²), which is the acceleration due to gravity on Earth, G is universal.

Despite being fundamental, G is notoriously difficult to measure precisely. Experiments like the Cavendish experiment have refined its value, but it remains one of the least precisely known constants in physics.

Masses (m₁ and m₂): The Source of Gravitational Pull

Mass is the source of gravity. The greater the mass of an object, the stronger its gravitational influence. In the force of gravity equation, both masses are multiplied together, meaning that if either mass doubles, the force also doubles.

For instance, Earth exerts a much stronger gravitational pull than the Moon because it has significantly more mass. This principle applies universally—from electrons to supermassive black holes.

Distance (r): The Inverse-Square Law in Action

The distance between two objects is squared in the denominator, making it a critical factor. This inverse-square relationship means gravity diminishes quickly with distance.

For example, astronauts in orbit around Earth still experience about 90% of Earth’s surface gravity. They appear weightless not because gravity is gone, but because they are in continuous free fall. This nuance is often misunderstood, but it stems directly from the force of gravity equation.

Applications of the Force of Gravity Equation in Real Life

The force of gravity equation isn’t just theoretical—it powers real-world technologies and explains everyday phenomena. From GPS systems to space exploration, its applications are everywhere.

Satellite Orbits and Space Missions

Every satellite orbiting Earth, from the International Space Station to GPS satellites, relies on calculations derived from the force of gravity equation. Engineers use it to determine orbital velocity, altitude, and stability.

For a circular orbit, the centripetal force required to keep a satellite moving in a circle is provided by gravity. Setting the gravitational force equal to the centripetal force gives:

G frac{M m}{r^2} = frac{m v^2}{r}

Solving for velocity (v) yields the orbital speed needed at a given altitude. NASA and ESA use advanced versions of this calculation for mission planning. Learn more at NASA’s official website.

Tidal Forces and Ocean Tides

The Moon’s gravitational pull, calculated using the force of gravity equation, is primarily responsible for ocean tides. Because the Moon is closer to one side of Earth, it pulls water more strongly on that side, creating a bulge.

A second bulge occurs on the opposite side due to inertia and the Earth being pulled slightly away from the water. This differential force—called a tidal force—is a direct consequence of the variation in gravitational strength across Earth’s diameter, as predicted by the equation.

Weight vs. Mass: A Practical Distinction

Many people confuse weight and mass. Mass is constant, but weight depends on gravity. Your mass is the same on Earth and Mars, but your weight changes because the gravitational force differs.

Using the force of gravity equation, we can calculate weight as W = m × g, where g = G × M_earth / r². So, while mass is intrinsic, weight is an application of the force of gravity equation in a planetary context.

Limitations and Criticisms of the Force of Gravity Equation

Despite its success, Newton’s force of gravity equation has known limitations. It works perfectly under most conditions, but fails in extreme environments, leading to the development of more advanced theories.

When Newtonian Gravity Fails: High Speeds and Strong Fields

The force of gravity equation assumes instantaneous action at a distance and does not account for the finite speed of light. In situations involving very strong gravitational fields—like near black holes—or when objects move at relativistic speeds, Newton’s model breaks down.

For example, Mercury’s orbit exhibits a precession (a slow rotation of its elliptical path) that cannot be fully explained by Newtonian gravity. This anomaly was one of the key pieces of evidence that led to Einstein’s general relativity.

The Need for General Relativity

Albert Einstein revolutionized our understanding of gravity in 1915 with his theory of general relativity. Instead of viewing gravity as a force, Einstein described it as the curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy.

In this framework, objects follow geodesics (the shortest path in curved space) rather than being pulled by a force. While more accurate, general relativity is mathematically complex. For most practical purposes, the force of gravity equation remains the go-to tool.

Quantum Gravity and the Search for Unification

One of the biggest unsolved problems in physics is reconciling gravity with quantum mechanics. The force of gravity equation is classical and does not incorporate quantum principles.

Theories like string theory and loop quantum gravity attempt to create a quantum version of gravity, but no complete and experimentally verified model exists yet. This gap highlights that even our best equations are incomplete.

Comparing the Force of Gravity Equation with Other Fundamental Forces

Gravity is one of the four fundamental forces in nature, but it behaves very differently from the others. Understanding these differences helps contextualize the uniqueness of the force of gravity equation.

The Four Fundamental Forces

The four fundamental forces are:

- Gravitational force

- Electromagnetic force

- Strong nuclear force

- Weak nuclear force

Each has its own governing equations and carrier particles (bosons). Gravity is mediated by the hypothetical graviton, though it has not yet been observed.

Why Gravity Is the Weakest Force

Surprisingly, gravity is by far the weakest of the four forces. For example, the electromagnetic force between two protons is about 10³⁶ times stronger than their gravitational attraction.

Yet, gravity dominates at large scales because it is always attractive and acts over infinite range, unlike the strong and weak forces, which are short-ranged. This makes the force of gravity equation essential for cosmology.

Unification Attempts and Theories

Physicists have long sought a “Theory of Everything” that unifies all four forces. While the electromagnetic and weak forces have been unified into the electroweak theory, gravity resists integration.

The force of gravity equation operates on a macroscopic scale, while quantum field theories describe the other forces at subatomic levels. Bridging this divide remains one of science’s greatest challenges.

Common Misconceptions About the Force of Gravity Equation

Despite being taught in schools worldwide, the force of gravity equation is often misunderstood. Let’s clear up some of the most persistent myths.

“Gravity Doesn’t Exist in Space”

This is a widespread misconception. Gravity absolutely exists in space. In fact, it’s what keeps planets in orbit and holds galaxies together.

Astronauts in orbit experience microgravity not because there’s no gravity, but because they are in free fall around Earth. The force of gravity equation still applies—they’re just falling at the same rate as their spacecraft.

“Heavier Objects Fall Faster”

Galileo famously disproved this idea by dropping objects from the Leaning Tower of Pisa (though the story may be apocryphal). In a vacuum, all objects fall at the same rate regardless of mass.

Why? Because while heavier objects have more gravitational force acting on them, they also have more inertia (resistance to acceleration). These two effects cancel out, resulting in the same acceleration—about 9.8 m/s² on Earth.

“The Force of Gravity Equation Explains Everything About Gravity”

While powerful, the force of gravity equation is an approximation. It doesn’t explain *why* gravity exists or how it propagates. It describes *how much* force there is, but not the underlying mechanism.

Einstein’s general relativity provides a deeper explanation, and quantum theories aim to go further. So, while the equation is incredibly useful, it’s not the final word.

Advanced Insights: Extending the Force of Gravity Equation

Modern physics has extended Newton’s original equation in various ways to handle more complex scenarios. These extensions maintain the core idea but adapt it for new contexts.

Gravitational Fields and Potential Energy

Instead of calculating force directly, physicists often work with gravitational fields and potential energy. The gravitational field strength at a point is defined as force per unit mass:

g = G frac{M}{r^2}

This is useful for mapping how gravity varies in space. Similarly, gravitational potential energy is given by:

U = -G frac{m_1 m_2}{r}

The negative sign indicates that work must be done to separate the masses.

Vector Form of the Force of Gravity Equation

The scalar version of the force of gravity equation gives magnitude, but gravity is a vector—it has direction. The vector form includes a unit vector pointing from one mass to the other:

vec{F} = -G frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} hat{r}

The negative sign indicates attraction, meaning the force on each object is directed toward the other.

Using Calculus for Continuous Mass Distributions

For objects like planets or stars, we can’t treat them as point masses in all cases. When calculating gravity from extended bodies, we use integration to sum the contributions from each infinitesimal mass element.

For example, the gravity outside a uniform spherical shell behaves as if all mass were concentrated at the center—a result proven using calculus and known as the shell theorem.

Educational Tips: Teaching the Force of Gravity Equation Effectively

Understanding the force of gravity equation is a milestone in physics education. Here are strategies to teach it clearly and engagingly.

Start with Everyday Examples

Begin with relatable experiences: dropping a ball, jumping, or feeling heavier on Earth than on the Moon. These intuitive examples help students connect abstract equations to real life.

Use simple demonstrations, like comparing the fall of a feather and a coin in a vacuum tube, to illustrate that gravity acts equally on all masses.

Use Visual Aids and Simulations

Interactive tools like PhET simulations from the University of Colorado (phet.colorado.edu) allow students to manipulate masses and distances and see how the force changes in real time.

Graphs showing how force decreases with distance help visualize the inverse-square law, making the abstract concept more concrete.

Incorporate Problem-Solving Exercises

Practice is key. Provide step-by-step problems: calculating the force between Earth and a person, comparing gravitational forces on different planets, or determining how force changes with altitude.

Encourage dimensional analysis to check answers and reinforce understanding of units and constants.

What is the force of gravity equation?

The force of gravity equation is F = G(m₁m₂)/r², where F is the gravitational force between two masses, G is the gravitational constant, m₁ and m₂ are the masses, and r is the distance between their centers. It describes how every mass in the universe attracts every other mass.

How does distance affect the force of gravity?

Distance has a powerful effect due to the inverse-square law. If the distance between two objects doubles, the gravitational force becomes one-fourth as strong. If the distance triples, the force drops to one-ninth, and so on.

Is the force of gravity equation still accurate today?

Yes, for most practical purposes—like engineering, astronomy, and education—the force of gravity equation is highly accurate. However, in extreme conditions (e.g., near black holes or at relativistic speeds), Einstein’s general relativity provides more precise predictions.

Why don’t we feel the gravitational pull from everyday objects?

We do, but it’s incredibly weak. Because the gravitational constant (G) is so small, only massive objects like planets and stars produce noticeable gravitational forces. The pull from a car or building is there, but far too weak to detect without sensitive instruments.

Can the force of gravity equation be used in space?

Absolutely. The force of gravity equation applies everywhere in the universe. It’s used to calculate the motion of planets, stars, galaxies, and spacecraft. Gravity doesn’t disappear in space—it’s what keeps celestial bodies in orbit.

From its humble beginnings with a falling apple to its role in launching satellites and understanding the cosmos, the force of gravity equation remains one of the most powerful tools in science. While newer theories have expanded our understanding, Newton’s elegant formula continues to serve as a reliable and essential model for gravitational interactions. Whether you’re a student, engineer, or curious mind, mastering this equation opens the door to comprehending the invisible force that shapes our universe.

Further Reading: